Peaceful and legal

In mid-1983 the Dutch Lower House passed a motion pressing for unilateral sanctions for the last time. From then onwards the Christian Democratic party in parliament no longer left open the possibility of an independent course on economic sanctions.

The ranks were closed up and dissident Christian Democratic MPs were forced to submit to party discipline, which resulted in the government of CDA and VVD, since 1982 under the premiership of Ruud Lubbers, no longer being urged to step up the pressure on South Africa. Jan Nico Scholten got nowhere anymore and left the Christian Democratic party, continuing as an independent MP. From now on, it became a matter of waiting for international agreement again. Foreign Minister Van den Broek put forward a 'two-track policy'. One track was international pressure, the other came down to: "supporting, according to our ability, social developments in South Africa directed at realizing fundamental reforms by peaceful means.".

The ranks were closed up and dissident Christian Democratic MPs were forced to submit to party discipline, which resulted in the government of CDA and VVD, since 1982 under the premiership of Ruud Lubbers, no longer being urged to step up the pressure on South Africa. Jan Nico Scholten got nowhere anymore and left the Christian Democratic party, continuing as an independent MP. From now on, it became a matter of waiting for international agreement again. Foreign Minister Van den Broek put forward a 'two-track policy'. One track was international pressure, the other came down to: "supporting, according to our ability, social developments in South Africa directed at realizing fundamental reforms by peaceful means.".

"There are lots of misunderstandings, caused mainly by the many thousands of kilometres separating both countries." (The Dutch ambassador in Pretoria, Carsten, explaining on South African television that the Dutch criticism of apartheid isn't so serious after all (1984)

What was visible in essence was an attempted return to 'dialogue' - not necessarily with the South African government, as The Hague was open for talks with "non-politically profiled organisations that operate within the bounds of South African legality". In effect, this meant that any other organisations did not qualify for assistance; it was thanks to Development Minister Eegje Schoo (VVD) that the humanitarian aid given to the ANC and SWAPO was exempted from this rule.

What was visible in essence was an attempted return to 'dialogue' - not necessarily with the South African government, as The Hague was open for talks with "non-politically profiled organisations that operate within the bounds of South African legality". In effect, this meant that any other organisations did not qualify for assistance; it was thanks to Development Minister Eegje Schoo (VVD) that the humanitarian aid given to the ANC and SWAPO was exempted from this rule.

The fact that the laws of South African 'legality' that the government referred to came down to censorship, state violence, gross human rights violations, racism and apartheid, and that in South Africa any voice raised against this situation was necessarily 'politically profiled', was not reflected in Dutch policy. The opposing sides in the South African conflict, meanwhile, appeared not overly interested in The Hague's view of the situation.

South Africa: 'Adapt or die'

In 1978 P.W. Botha, the former South African Defence Minister, was appointed Prime Minister. He steered a course for the apartheid system to be patched up by adjustments that might help restore South Africa's tarnished international reputation. But this course was as much dictated by domestic concerns as by international considerations. South African business, for instance, wanted to see an end to the inefficient system in which certain classes of jobs were being reserved for whites. And by placating parts of the non-white population, granting them limited privileges, the regime hoped to neutralize the growing appeal of the liberation movement.

In 1978 P.W. Botha, the former South African Defence Minister, was appointed Prime Minister. He steered a course for the apartheid system to be patched up by adjustments that might help restore South Africa's tarnished international reputation. But this course was as much dictated by domestic concerns as by international considerations. South African business, for instance, wanted to see an end to the inefficient system in which certain classes of jobs were being reserved for whites. And by placating parts of the non-white population, granting them limited privileges, the regime hoped to neutralize the growing appeal of the liberation movement.

For whites it had become a matter of 'adapt or die', according to Botha. A new Constitution was to give the vote and a semblance of shared power not to the black majority, but to 'Indians' and 'Coloureds'. To this end the two groups were to get their own Chamber besides the existing white parliament. In keeping with apartheid thinking each Chamber in the proposed tricameral parliament was supposed to handle mainly the group's 'own' affairs.

To Botha this formed part of a 'total strategy' against the ongoing 'total onslaught' on South Africa. In his eyes Moscow was the evil demon behind the increased strength of the liberation movement. Under his rule, South African politics came much more under the influence of the military, and with the new Constitution of 1984 Prime Minister Botha himself was made President with far-reaching powers. The tricameral parliament was installed after elections boycotted by almost all of the new voters.

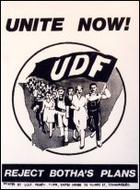

The UDF: a new phase

In 1983, after a call by the anti-apartheid activist Reverend Allan Boesak - who had studied in the Netherlands in the early 1970s - some 400 organisations in South Africa joined forces against apartheid. Together they formed the United Democratic Front (UDF), in order to act on the constitutional pseudo-reforms in the first place. Trade unions, women's and students' organisations, cultural and sporting associations, Christian and Muslim organisations from the whole of South Africa all took part.

In 1983, after a call by the anti-apartheid activist Reverend Allan Boesak - who had studied in the Netherlands in the early 1970s - some 400 organisations in South Africa joined forces against apartheid. Together they formed the United Democratic Front (UDF), in order to act on the constitutional pseudo-reforms in the first place. Trade unions, women's and students' organisations, cultural and sporting associations, Christian and Muslim organisations from the whole of South Africa all took part.

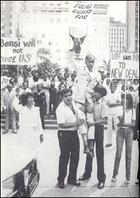

Hundreds of additional organisations joined the UDF in the years that followed. From then on, the Dutch solidarity movement was to a greater extent able to direct its support, rather than to the exiled liberation movements, to the resistance within South Africa itself. Botha, on a trip through Europe in 1984, did not call at the Netherlands. The Hague urged the European Community not to receive him in Brussels. There were demonstrations in the Netherlands in 1984 against Botha's European trip, and against the intimidation of UDF activists in South Africa.

Botha, on a trip through Europe in 1984, did not call at the Netherlands. The Hague urged the European Community not to receive him in Brussels. There were demonstrations in the Netherlands in 1984 against Botha's European trip, and against the intimidation of UDF activists in South Africa.

There were also demonstrations against the attempts of the South African army to quell the growing movement in the townships against apartheid by force. The ANC now called for a people's war against Botha's ruthless policies; the call to make South Africa 'ungovernable' was being heard indeed.